Cricket was one channel of Westernisation during British colonial rule. But it was also a medium for Ceylon to challenge the ideas of racial superiority so prevalent among the island’s ruling Britons. By the 1920s the Ceylonese team were proving their superiority over the Europeans in annual matches.

The Maharaja of Vizianagram was so captivated by all-rounder Edward Kelaart in the early 1930s that he invited him to play for his Indian team. Meanwhile, F. C. de Saram made the headlines when he scored 128 runs out of a total of 218 for an Oxford University side that faced the touring Australians in May 1934.

These early signs of competence were supported in the immediate post-World War II scenario from 1945 when several touring sides visited Ceylon – viz. an Australian Services team captained by Lindsay Hassett in December 1945; the Madras CA in January 1947; the winners of the All-India tournament – Holkar CC – in April 1948; and West Indies and Pakistan in 1949.

The local batsmen displayed their capacities on several occasions. After Madras CA piled up a massive 521 runs for 7, Mahadevan Sathasivam carved out a scintillating 215 runs in 248 minutes against them in January 1947. Indeed, Sathasivam impressed all the visiting teams and local spectators with his majestic range of strokes.

Makkin Salih scored 111 not out for Ceylon in a total of 257 for 4 after Holkar had piled up 475 for 8. And Mahes Rodrigo starred for Ceylon in one match against the West Indians with 135 not out.

C. I. Gunasekera was one of Ceylon’s most punishing batsmen. He scored 212 in one of the first Gopalan Trophy games against Madras Presidency in 1952/53. He also amassed 135 runs in a huge

4th wicket partnership with Keith Miller when a Commonwealth XI mauled an MCC team by an innings at the P. Sara Oval in 1952.And Channa Gunasekera’s 66 not out in a whistlestop match against the Australians at the Oval in Colombo in March 1953 initiated a lifelong friendship with Keith Miller.

Noticeably, the stand out Ceylonese achievements in these early years were in batsmanship rather than bowling. But one must not neglect wicketkeeping: Mervyn Fernando and Ben Navaratne displayed exemplary slickness behind the stumps in matches played against the touring sides in the 1940s, and set the tone for a long line of impressive keepers such as H. I. K. Fernando, Ranjit Fernando and Mahes Goonatilleke.

The lodestar remained England. Cricketers with connections and requisite capacities penetrated the English county circuit through the university system or other levers.

Laddie Outschoorn, Stanley Jayasinghe, Gamini Goonesena, Dan Piachaud, P. I. Pieris, Clive Inman, Mano Ponniah and Vijaya Malalasekera entered these portals between the 1940s and ’60s. And Gamini Goonesena (of Cambridge and Nottinghamshire) went on to captain MCC sides in the 1960s.

Meanwhile, a Ceylon team skippered by a young Michael Tissera beat a touring Pakistan side in a low scoring encounter in August 1964 – in large part because of paceman Darrell Lieversz, and spinners Neil Chanmugam and Anurudda Polonowita.

When Tissera led a squad on a tour of India immediately afterwards, they lost the first two unofficial Tests badly but upended the Indians through a bold declaration and good bowling in early January 1965.

Sponsored by India and Pakistan, Ceylon secured the status of Associate Member of the International Cricket Council (ICC) in 1965. Given Goonesena’s clout with the MCC, the island cricketers were now on the cusp of a prestigious tour of England.

But two problems confronted those committed to such a programme.

One was the shortage of foreign exchange. The other was the unwillingness of the then United National Party (UNP) government to release funds for the tour. That reluctance marks a third factor – a circumstance that seems ridiculous in hindsight.

The restraining forces were the political currents and class forces set in train by the general election of 1956, which was marked by the Sinhala Only agitation associated with S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike. By 1964/65, most of the Marxist parties were also part of this bandwagon while the English language was marked out as an abhorrent kaduwa (sword) by the nascent petite-bourgeoisie and working classes.

Cricket was among the alien unwanted to the nativists driven by this current of thinking.

Despite these circumstances, the plans to tour England were moving ahead when machinations initiated by a small clique of cricketers led to the gerrymandering of the squad chosen for the tour.

This plotting spawned an uproar. In the end, the tour was cancelled and that story is a complex one. What remains pertinent here is the fact that the plotters were not only greasing their own interests (meaning selection) but seeking to overthrow the Royal-Thomian ascendancy in cricket at that point.

The jealousies directed at the Royal-Thomian and Westernised sets at the pinnacles of the local cricketing scene in the 1960s occurred at a stage when cricketers from outstation towns and beyond the leading Colombo schools were on the cusp of breakthroughs into the top rungs.

Nor did the drive for the cricketing heights by fair means or foul comprehend the foundations upon which specific streams of cricketers had secured their success on the playing ground.

The reasons for the hegemony over cricket from the early 1930s onwards exercised by Colombo and within the metropolis – by a few schools such as Wesley, Royal and S. Thomas’ – included the following: decent turf wickets and other institutional conditions; and good coaching and a buildup of skills via intergenerational legacies.

By way of illustration therefore, with Lassie Abeywardena as Under 16 coach of S. Thomas’ from circa the 1950s, the fruits for the school and eventually Sri Lanka were immeasurable. The Thomian batsmen of the ’60s were among the most technically proficient players of their time – and I speak from experience in playing with and mostly against them.

Allowing for a few exceptions, most cricketers in the period extending from 1887 to the 1960s originated from schools in Colombo, although Moratuwa (virtually a suburb of the city), Kandy and Galle also provided a few.

However, the spectator public was larger and extended to some segments of the working classes in the main towns throughout the island.

This outreach and the continuing extension of popular interest in the sport were fostered by access to education in good schools for all classes, in the principal towns and their fringes; the popularity of interschool cricketing encounters; and Radio Ceylon’s initiative in broadcasting the Ashes from 1938 onwards.

When nativists and Marxists targeted cricket as an adjunct of the Westernised English language universe in the 1960s, they were inattentive to the subterranean changes that were undermining this situation – changes that came to fruition by the 1980s and rendered cricket into a popular activity, marking Sri Lanka’s place in the international sporting arena.

What induced such a transformation?

Here are some conjectural answers…

Perhaps the most significant force behind this shift was the introduction of Sinhala language broadcasts of the annual blood match between Ananda and Nalanda around the year 1967 by Neville Jayaweera who headed the Ceylon Broadcasting Corporation (CBC). A whole new vocabulary had to be gerrymandered for this purpose with Dr. Vinnie Vitharana and Karunasena Abeysekera assisting Palitha Perera of the CBC (a former Nalandian cricketer) to fashion the terminology – a process that was imprinted far and wide by the sonorous Sinhala voice of Premasara Epasinghe.

Schools in Kandy, Moratuwa and Galle produced a few cricketers of the highest competence between the 1940s and ’60s, and this trend expanded in subsequent decades.

One witnessed Ajit de Silva, D. L. S. de Silva and D. S. de Silva – all players from the Southern Province – earning a spot in the representative Sri Lankan squads chosen for tournaments in England in the 1970s where the others in the squad were from a mix of Colombo schools.

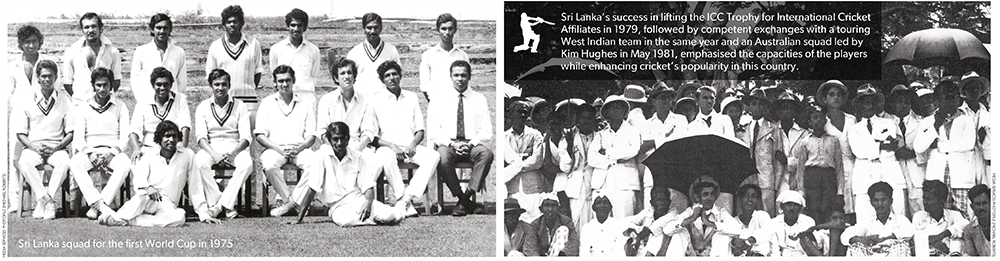

Sri Lanka’s success in lifting the ICC Trophy for International Cricket Affiliates in 1979, followed by competent exchanges with a touring West Indian team in the same year and an Australian squad led by Kim Hughes in May 1981, emphasised the capacities of the players while enhancing cricket’s popularity.

The ODI matches in the island against India and the West Indies in the 1970s, and the series versus the Australians in 1981, saw pulsating matches before packed crowds where the local cricketers were competitive.

And to cap it all, intelligent lobbying orchestrated by the then president of the Board of Cricket for Sri Lanka (or Board of Control for Cricket in Sri Lanka – BCCSL) Gamini Dissanayake in England capped the on-field performances and secured full ICC Test status for Sri Lanka in mid-1981.

And there was the coincidental advent of colour TV in Sri Lanka in the year 1981. This enabled the presentation of Sri Lankan cricket matches in flaming colour to a much wider audience across the island. These happenings promoted wider public attention to the work of Sri Lankan cricket teams.

However, the second Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP) insurgency of 1987-89 and sporadic bomb strikes by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in Colombo from 1987 onwards hindered the opportunities there were for teams to display their capabilities in a favourable home environment.

Luckily, the ICC Cricket World Cup in 1996 was played on the Indian subcontinent, and the squad – led by Arjuna Ranatunga and coached by Dav Whatmore – displayed acumen and skill in proceeding to lift the trophy.

Cricket’s appeal among a wider public across class barriers was now assured. But this appeal didn’t extend to a large proportion of the Sri Lankan Tamil population who were alienated from the political dispensation.

Tamil cricketers drawn from their middle-class residents in Colombo and Kandy had provided some of the leading players from way back but changes to university admission criteria and political currents discouraged these inclinations from the ’70s. The pogroms of 1977 and 1983 weaned their peoples away from supporting cricket.

In Colombo, the Tamil Union had to rely mostly on Sinhalese players and hardly any Tamils represented Sri Lanka in the 1980s. Ironically however, in the last 25 years or so, three Tamils – viz. Muttiah Muralitharan, Russell Arnold and Angelo Mathews – have featured in star roles.

The broadening of reach is indicated by cricketers from Matale, Kegalle, Kurunegala, Chilaw, Negombo, Rathgama, Ambalangoda, Matara and Debarawewa in the Hambantota District who have represented leading XIs over the last 30 or so years.

And when a fisherman’s son from Matara, no less than Sanath Jayasuriya, becomes a match winner on several occasions and the captain of Sri Lanka, one can argue that the democratisation of cricket has been both deep and wide.

And there’s been political one-upmanship and its benefits too…

The popularity of cricket encouraged leading politicians to use it as a platform to gain prestige.

Dissanayake was secure in his role as President of BCCSL but nevertheless, built up Asgiriya in Kandy as a Test ground to consolidate his popularity in home terrain. Tyrone Fernando promoted a venue in Moratuwa, which was then named after him. And ex-president Ranasinghe Premadasa was the boldest of the lot – he built a new stadium with lights in a slum area near his birth patch. Whatever the motives, this has turned out to be a long-term godsend that enables day-night matches to be played in the commercial capital.

There’s been an abundance of musical chairs in governance and cricketing records too…

The Board of Control for Cricket in Ceylon, set up in 1948, was a governing body constituted by named cricket clubs. Always in parlous financial straits, it relied on patronage from its elected presidents – usually big men with big pockets and political links.

This situation changed in 1996, following Sri Lanka’s triumph in the World Cup – the coffers expanded enormously and entrepreneurs were attracted to the presidency of the BCCSL (now Sri Lanka Cricket – SLC). A spoils system that set up oligarchic regimes developed and in consequence, the central government has intervened on several occasions and set up a board of its own or the sports minister has taken charge through an appointee.

The outcome has been a game of musical chairs in governance, sometimes aggravated by ministerial whim or changes in the country’s government in the aftermath of elections.

Of course, changes to the cricket board mean changes in selection committees. So from 1997 to early 2019, Sri Lanka has had almost as many governing bodies as years. It is a marvel therefore, that the Sri Lankan cricket teams have been for the most part competitive in the field during this period.

As remarkably, the cricketing generations of the 1990s to 2018 can point to some remarkable cricketing records generated by a team or certain players. Note this listing...

First, there was the highest total ever (952 for 6) in a Test match – at the R. Premadasa Stadium against India.

Sri Lanka also recorded the two highest partnerships in Tests: 624 runs for the 3rd wicket between Mahela Jayawardene and Kumar Sangakkara versus South Africa – on 26 July 2006 at the SSC grounds; and 576 for the 2nd wicket between Jayasuriya and Roshan Mahanama at the R. Premadasa Stadium against India on 2 August 1997.

And the Bradman among bowlers, Sri Lanka’s Muralitharan took 800 Test wickets in 230 innings at an average of 22.7 with a record number of 5 wicket hauls.

The star all-rounder in 50 over cricket, Sanath Jayasuriya is the only batsman thus far to score over 12,000 runs and capture more than 300 wickets in ODI internationals.

Winning the World Twenty20 final in Dhaka on 6 April 2014 after being runners-up in 2009 and 2012 also warrants mention.

And on top of Sri Lanka’s magnificent World Cup victory in 1996, reaching the final of the competition on two more occasions (in the West Indies in 2007 and on the subcontinent in 2011) is no mean feat when compared to the fortunes of England for example, in this form of the game.

And there, by the grace of the deities, lies the contradictory tale of cricket in Sri Lanka