He had three pips on his shoulders’ gauntlets; first and foremost, he was a cricketer – it was clearly his passion; he was also a medical doctor – a profession he pursued with vim, vigour and vitality; and last but by no means least, he was a soldier – a brave vocation, which pastime stood him in good stead behind the proverbial stumps – and that’s putting it mildly.

There’s no little irony in the image of a healer behind the stumps. And the paradox is compounded when one recalls how the act of stumping his victims challenged the composure of this military man.

Be that as it may, H. I. K. Fernando could readily dispense with his pills and stethoscope, as well as the brigadier’s epaulettes. That was when he caught, stumped or appealed vociferously for an LBW. That was when ‘Herbie’ (as he was fondly known) went bananas!

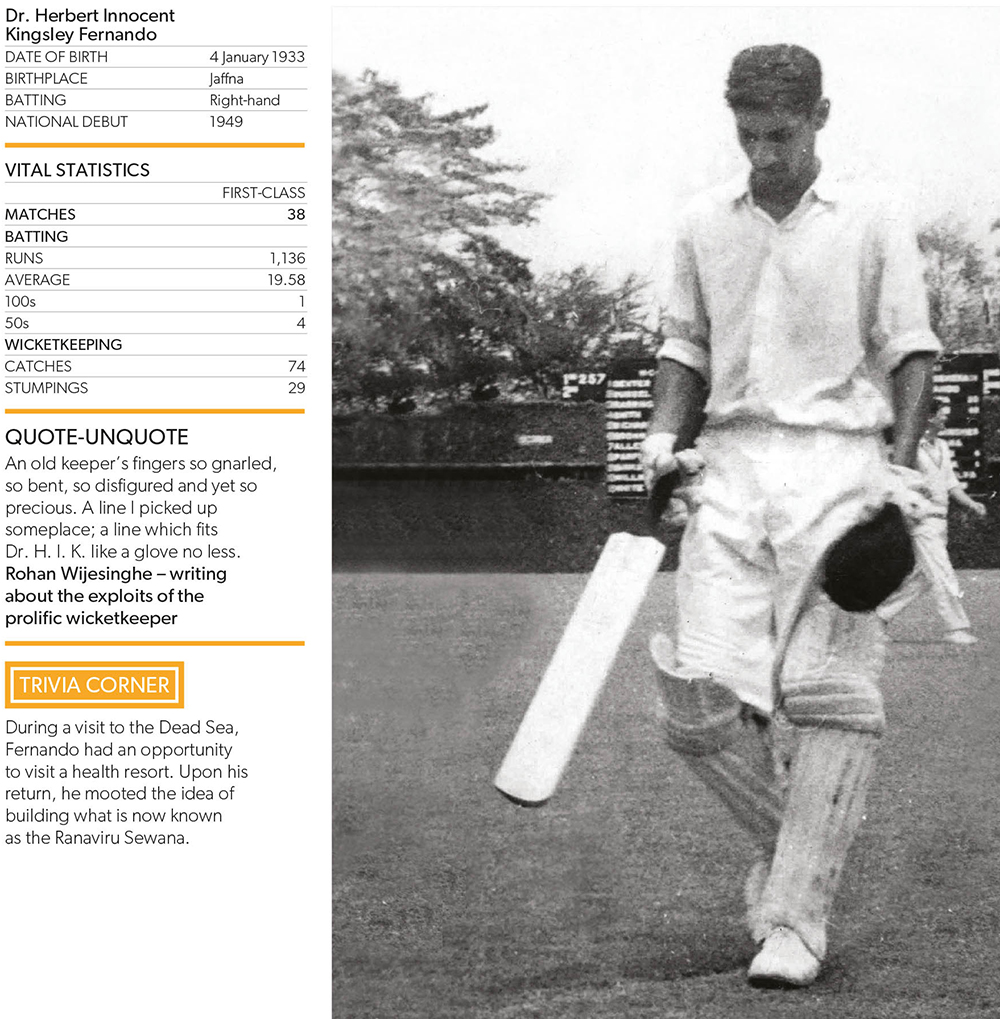

This is the story of an officer and a gentleman; a doctor in the army who was also Ceylon’s number one wicketkeeper from 1953 to 1970. A product of St. Peter’s, he captained the school side in 1951 and ’52, and won the Schoolboy Cricketer of the Year award in his second term as skipper.

The doctor in waiting was first seen in a first-class match in 1953, the same year in which he made his international debut in a day game against a touring Australian team.

As for his time in the military, Fernando has recalled an occasion when he was sent to Jaffna along with 12 other brigadiers and the aircraft in which they were flying developed engine trouble over Kalpitiya. “That was the one time I was actually facing the possibility of death. We survived; and it was after this incident that it was decided to limit the number of ranked officers flying in a single plane,” he revealed.

A disciplined terror behind the wickets, ‘H. I. K.’ (as he was also known) could bat as well. It shouldn’t surprise anyone who is unfamiliar with this bygone era to know that when Ceylon beat India on the 1964/65 tour, the man who took four catches behind the wicket and was responsible for three stumpings also registered the islanders’ second highest score (38 not out).

A prognosis of a 102 not out in the Gopalan Trophy of 1965/66 (his only first-class century) helped Ceylon secure a draw. And here at home in the P. Sara Trophy, he dashed off 10,000 runs.

Fernando led the Ceylon team that toured Malaya and Singapore in 1957. Fast forward to 1982, and he was the chairman of selectors when Sri Lanka first played Test cricket – although it might be to his eternal regret that H. I. K. picked himself to captain the national side to tour England in 1968 – a tour that was cancelled shortly before its scheduled commencement.

Controversy aside, it was his surgical precision with the gloves behind the stumps that won him both respect and numerous accolades.

So impressive was H. I. K. that an erstwhile Indian chief selector ranked him above any wicketkeeper on the subcontinent. In fact, he went as far as to say that Fernando was “Asia’s best stumper.”

And this was an opinion shared by English journalist Leslie Smith who wrote after watching Herbie keep wicket against an MCC team in 1965 that he was “the best wicketkeeper in Asia.”

The iron fists in velvet gloves gave back to where he got his start thanks to a lengthy stint as Peterite coach. But only those who had seen him at work with a doctor’s determination, dedication and devotion, and a professional soldier’s discipline to boot, would know that the greased lightning behind the stumps was not only the team’s metronome but also that of an officer and a gentleman.

On that fateful day in July 1983 when 13 soldiers were ambushed and killed, triggering riots that eventually led to a protracted civil war of nearly three decades, Dr. H. I. K. Fernando had the unenviable task of obtaining death certificates and sending the bodies of slain soldiers to their respective families. His bravery therefore, had no boundaries